I hate to think how close I came to not doing a Dick Cavett Television Show with John Neihardt. And not getting to meet and know him.

When you get your talk show and you come from, say, Nebraska, you’ll find that people back home have great ideas for guests you should have on.

Some from your own home town. “…Uncle Ned,” who you’re assured is “far funnier than all those so-called comedians on television,” and who kept the Epworth League Picnic in stitches with his imitation of Charlie Chaplin, a meadow lark, and his playing two accordions and a harmonica all at the same time.

Someone else has a daughter whose singing gifts exceed “all those famous ones on television.” And the mayor’s son who can simultaneously tap dance and recite Shakespeare, “like nobody’s business.”

So I was wary when my parents said that an elderly local man had held our living room full of people enthralled for two hours, talking and reading his poetry. Correction: reciting his poetry, by the yard, from memory, at nearly ninety years of age. Here we go again, I thought.

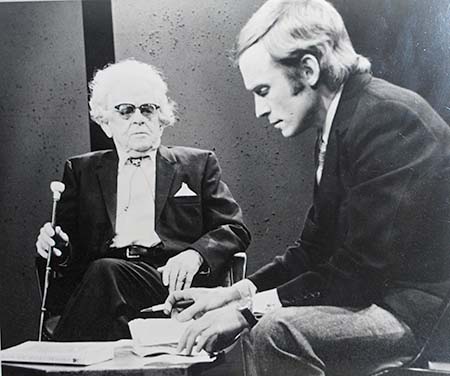

But that particular urging, from several quarters, seemed to have a more convincing quality somehow. I decided to take a chance on this man named Neihardt. At least he didn’t play the accordion. I couldn’t have guessed that for years to come I’d be told he was the most wonderful guest I ever had.

I convinced my staff and producer, flew to Nebraska, met with him in Lincoln for a delightful afternoon chat and, the next day, we taped for nearly two hours in Omaha. Just two chairs, a table, and a six-pack of beer for… one of us. I told him I couldn’t believe he was 91 and he said he couldn’t believe it either. As taping went on, I could see the profound effect he was having on bystanders in the studio as he wove his tales and stories in that mesmerizing way of his, taking you back in time. He told his immortal story of Black Elk and the vision this mystic and noble American Indian had so fortunately settled upon Neihardt as the man with the skills and understanding to bring his colorful and spiritual vision to the world.

A limo driver who’d driven me to the taping had stood by and watched. He was a sort of tough-looking guy you might cast to play a security guard or a cop. When we finished after about two hours, I asked how he had liked it. He said, “I never expected to see and hear anything like that in my life. When that old guy recited that “Death of Crazy Horse” poem I was bawling like a baby.”

Neihardt’s masterpiece Black Elk Speaks was a title familiar to me from earliest boyhood library visits, but I hadn’t opened it or checked it out. Being a kid, I’d seen it on the shelf of the “Indians” section, but from the title I mistakenly thought it sounded like a bunch of speeches and, being a kid, I was vastly more interested in pictures of fierce warriors, campsites, tomahawks, scalpings, mounted Sioux and Cheyenne in full regalia and, especially, accounts of bloody battles. Black Elk did not, until much later, speak to me.

Sitting there in Omaha with Neihardt, if I could somehow have peeked into the future a couple of decades and seen the unimaginable picture of myself doing a television show from glamorous and only-dreamed-of New York City, chatting with an author of a book called, “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee,” I wouldn’t have believed any of it. It would have had no more reality than a peyote episode.

The author, Dee Brown. mentioned seeing my show with Neihardt, adding, “Thousands of books have been written about Indians, and there are many fine ones. But if you could only preserve one book about the American Indian, it would have to be “Black Elk Speaks.”

The morning after the Neihardt show aired, I was told by the people in whose home he lived in Lincoln, the Julius Youngs, that he was found the next morning, fully dressed, sitting mournfully in the living room. Mrs. Young asked what was wrong. He moaned, “I guess it wasn’t very good. Nobody has called.” She tried to assure him that maybe later someone might call. Later, when it was no longer 5:45 in the morning.

Calls came.

That same post-Neihardt next morning, in New York City, my producer’s wife found herself among about twenty people outside the big bookstore across from Carnegie Hall, waiting for it to open. When it did, they all went to the yard high stack of Black Elk Speaks the canny owner had put on display, having seen the show the night before. She bought her copy and then watched as the stack went down, one by one, to zero. A book decades old was re-born and John’s—I mean, Dr. Neihardt’s—publisher, the University of Nebraska Press, had to literally run the presses around the clock. Fan mail poured in about the show and new Neihardt readers were virtually tearful in their gratitude. I still hear about it.

One benefit for me was getting to discover and read John’s other prose works such as Eagle Voice Remembers, The River and I and Splendid Wayfaring And in reading his glorious poetic works A Cycle of the West and Lyric and Dramatic Poems.

I find that having heard him read the Crazy Horse poem, I hear that lyric voice of his in my mind’s ear when reading.

Meeting and getting to know John Gneisenau Neihardt was one of those thrills of a lifetime. It gladdens me that he was able—thanks to those who had urged me to do a show with him—to live on long enough to enjoy a large dose of well-deserved, and much relished, celebrity in his final years, and that his large body of rich works can now reach a still growing audience of readers who might have missed them.

I’m grateful to the gods that I chose to put John Neihardt on my show. What if I had chosen Uncle Ned instead? Accordions AND a harmonica?

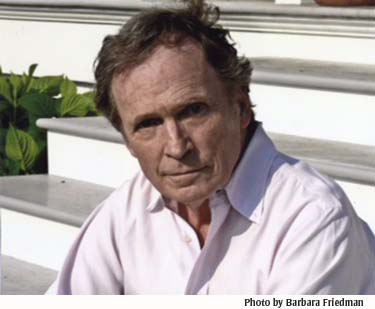

Dick Cavett