This paper was presented by Coralie Hughes, grand-daughter of Mona Neihardt at the annual Neihardt Spring Conference, April, 2002

(Hilda Neihardt, Coralie’s Mother and the daughter of Mona Neihardt, wrote a book telling the love story of the life of Mona and John titled: The Broidered Garment)

“And Thank You, God . . . For Everything”

If one endeavors to be fair, the life and works of John G Neihardt cannot be fully appreciated or understood without knowing his wife and comrade, Mona, so profound was her impact on those so-heralded literary achievements. No discussion of Mona will not soon involve her husband, John, so devoted was she to him and to his art. Through a long and often difficult life together they achieved an entwined intellectual and spiritual connectedness. As a distraught John would say after her untimely death “she built herself into the walls of my world.” That Mona was archetypically loyal and devoted as wife, mother and grandmother is profoundly true of her. But she was also a powerful person and a highly talented artist in her own right. Our focus today is to appreciate Mona, the artist, Mona, the extraordinary.

Mona was born Ada Ella Martinsen on May 26, 1884 in New York to her extraordinarily vivacious American-born mother Ada Ernst Martinsen and her European-born financier and railroad magnate father Rudolph Martinsen. Despite his youth, Rudolph’s integrity was so well established that he was empowered to represent in America the interests of several Dutch banks. At twenty-two he had the privilege of signature of the Boissevan house. Later he became president of the MKT Railroad, president of the Maxwell Land Grant, and one of the financiers of the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

Rudolph and Ada Ernst met on a steamer as Ada was on her way from the United States to Germany to attend drama school. By the end of the transatlantic voyage, Ada had so charmed the serious Rudolph with her wit and her impulsive gaiety that Rudolph proposed marriage to her and she accepted. They were married shortly thereafter in Germany. Their children were Ottocar, Harold, Rudi and Mona.

So, our Mona was a child of wealth and privilege. As a child, Mona shuttled back and forth across the ocean with her parents from their lavish 5th Avenue house in New York to hotels in France, to their chateau in the Black Forest of Germany which they called Vhromberg, all the while attended by French and German governesses. But our Mona did not like her life as a child. She hated the stream of governesses and the ocean voyages. Mona proclaimed early that when she grew up and married she intended to take care of her babies herself, a notion sure to have met with the amused derision of her mother’s friends. But Mona did something else at a young age that set notice to the world that here was a truly original and independent thinker: She changed her name Ada, which she shared with her mother, to Mona.

Mona was particularly devoted and attached to her father. She shared his considerable musical talent; he was an accomplished pianist. She was devastated when he died in only his early 40’s in 1892, and never got over the loss. Mona was only 8 at the time. After her father’s death, her education shifted from private schools in New York to Dresden, where she studied voice and violin under Konzertmeister Petrie of the Dresden Opera. She also learned to speak three languages.

At 18, though prepared to attend Bryn Mawr, Mona found a new interest in art. Amusing herself down in the kitchen of the New York house, she one day modeled a head of her brother Ottocar with dough the cook had mixed for bread. Her mother was struck by the excellence of the likeness and arranged for Mona to study sculpture with Frank Edwin Elwell, then Curator of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mother Ada must have had to do some convincing of Elwell to get her daughter in such a prestigious post for training, for he felt the socialized timidity of most women compromised their artistic ability and their feminine presence in the studio complicated the master-pupil relationship. Before Elwell would accept Mona as his student, he first granted her an audition in a rather unorthodox fashion. In his studio was a partially finished statue of a horse and rider. On his way out to lunch, Elwell casually told Mona to complete the sculpting of the rider’s boot. Her craftsmanship must have proved satisfactory, for Elwell immediately accepted her as his pupil.

At 18, though prepared to attend Bryn Mawr, Mona found a new interest in art. Amusing herself down in the kitchen of the New York house, she one day modeled a head of her brother Ottocar with dough the cook had mixed for bread. Her mother was struck by the excellence of the likeness and arranged for Mona to study sculpture with Frank Edwin Elwell, then Curator of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mother Ada must have had to do some convincing of Elwell to get her daughter in such a prestigious post for training, for he felt the socialized timidity of most women compromised their artistic ability and their feminine presence in the studio complicated the master-pupil relationship. Before Elwell would accept Mona as his student, he first granted her an audition in a rather unorthodox fashion. In his studio was a partially finished statue of a horse and rider. On his way out to lunch, Elwell casually told Mona to complete the sculpting of the rider’s boot. Her craftsmanship must have proved satisfactory, for Elwell immediately accepted her as his pupil.

The “experiment,” as Elwell referred to his acceptance of Mona as a pupil, impacted him as favorably as it did Mona, for he wrote a long article entitled ‘MART’ in an October 1905 edition of The Arena. Elwell recalled an early lecture to Mona: “There is no reason to fear anything in this world, least of all the clay you are working with. See with your own eyes, and make what is in your own mind, regardless of what others have made. Fear is the beginning of the end in an artist’s career, and the cause of woman’s mediocrity. Do not fear your master, do not set him up on a pinnacle to worship in a stupid, feminine way… When you chop clay or wash the floor, remember that it is to be as well done as your modeling, so that you get into the habit of doing work thoroughly, and not shifting your real hard work on to some assistant.”

Elwell continued his recollections, “Among the first things taught this slip of a girl was to say something forceful with all thepower of her soul; to break up her bad work as regardless of it as though it had been some evil thing, and straightway to forget it. It was wonderful how this teaching of courage and animal power, instead of weak politeness of attitude toward one’s art, lifted this young woman out of the commonplace, and made her as interesting to teach as a man. It was very hard work at first to teach such brutal things to a refined nature. Each day she was [intellectually] ‘rough-housed’ much as one would a boy. She finally saw what was intended, and though she said nothing she set to work—hard work—to try and drive away feminine timidity and to attack her clay with a boldness and vigor that was truly delightful to one who had regarded women as a nuisance in studio life.”

Elwell describes the physical transformation in Mona as well: “Mart’s hands, when she first appeared at the studio, were much like those jelly-fish arrangements that are of so little use in society, and are so expensive to maintain in idleness, but now her hands are strong and fine tools with which she can master the clay and put up great masses so that she can interpret her inspirations in a big way. They are the hands of a woman who is doing her own thinking and can destroy as well as create. They are the servants of a brain that sees clearly the larger forms in art, and they do not tire in the search for those forms.”

Elwell, the sculpture master, triumphantly recalls Mona’s rise to good art: “And now, at nineteen, she makes a statue called ‘Motherhood,’ and no other hand has touched it. None but her own strong hands have labored on that clay, have torn and demolished part after part, to rebuild in better form, with greater meaning, with more vitality. It is a wonderful statue, not unlike Rodin in treatment, but yet thoroughly original, and her own: it has the stamp of her own individuality. It is not difficult to feel the intensity of the mother-love in the way the woman holds to her breast the infant babe. Her left hand is drawn away by a serpent, as though an evil tendency had for a moment taken possession of her; but the mighty mother struggle is seen in the head thrown back and the eager intensity of expression, as she tries to cover with her body the infant from the harm of the world. And so Mart has taught us a lesson, both by her own sweet, strong, pure life, and in her statue of ‘Motherhood.’ Think you that she is any the less a lady because she has learned to use the strength and handling of the man, or that she will the more easily be led to the evil of life? She has risen to the plane of mental virtue through the ‘rough-housing’ of the masculine mind, she has a wider view of life and is in no fear of man or of her clay. Are not these great qualities for one so young?” They are also the great qualities of physical and intellectual strength and stamina necessary for the future wife of John Neihardt.

Honors for her art came rapidly for Mona. At 20 she received a thousand dollars for her first order, the bust of a Fifth Avenue banker. Elwell referred to Mona as the most gifted of her contemporaries. When Edwin Elwell had taught Mona all he could, he urged her to go to Paris to study with Rodin, the most highly acclaimed master of the time. Though by that time family finances were tight, Mona’s mother Ada went to work again to make it happen for her daughter. She gained permission for Mona to have an audience with Rodin and scraped together the money to make it possible. Mona set sail once again for Paris in 1905.

Mona recalled her first meeting with the great artist, “I walked over to him and said ‘I have come across the Atlantic to see you’. He smiled and said ‘Je suis enchantee, mademoiselle’.” Mona explained to Rodin that Elwell had sent her to Paris in order to “gain that quality and knowledge which characterized Europe as the cultural center of the world.” After examining several of the young sculptress’ works, Rodin accepted her as his pupil. Under his instruction Mona worked for two years. From Rodin she learned the technique which enabled her to sculpt from memory. It was Rodin’s policy to work with a model in the morning, then rely on memory in the afternoon.

Most of her time in Paris was spent in working alone, another suggestion of the master. In her tiny, skylighted studio just off the Montparnasse, Mona worked from dawn until evening each day. The problem of leaving her work for the noon meal was soon solved when a friend advised the young girl that two raw eggs would easily take the place of a regular meal. So, two raw eggs, whipped and seasoned with salt and vinegar, soon became her steady noon diet.

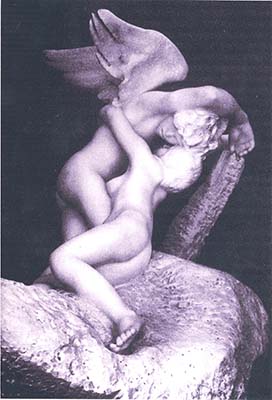

From Rodin, Mona no doubt received the master’s perspective on Art. “Art is contemplation. It is the pleasure of the mind which searches into nature and which there divines the spirit by which Nature herself is animated… Art is the reflection of the artist’s heart upon all the objects that he creates.” Mona no doubt learned what Rodin learned from his master: “When you carve, never see the form in length, but always in thickness. Never consider a surface except as the extremity of a volume, as the point, more or less large, which it directs towards you. In that way you will acquire the science of modeling.” Rodin further explains “I force myself to express in each swelling of the torso or of the limbs the efflorescence of a muscle or of a bone which lies deep beneath the skin.” Notice the tension in the muscles that express the physical effort of great contemplation in The Thinker.

And Rodin again: “And so the truth of my figures, instead of being merely superficial, seems to blossom from within to the outside like life itself. “Note in Cupid and Psyche the touchable softness and smoothness of the skin that expresses the sensual love.

“If the artist only reproduces superficial features as photography does, if he copies the lineaments of a face exactly without reference to character, he deserves no admiration. The resemblance which he ought to obtain is that of the soul; that alone matters; it is that which the sculptor or painter should seek beneath the mask of features. In a word, all the features must be expressive, that is to say, of use in the revelation of conscience.”

“All is idea, all is symbol. So the form and the attitude of a human being reveal the emotions of its soul. The body always expresses the spirit whose envelope it is.” One can sense the totally different personalities and characters of Chavannes and Falguiere as made permanent in Rodin’s sculpture of the two men.

These two years of study and hard work were climaxed by an exhibit at Le Salon des Beaux Arts in which two of her pieces were accepted. One, a life-sized model called “The Maiden,” was a figure of a young woman, blindfolded and struggling with the bonds of conventions. Mona called it “The Soul Striving.” Already in her work, Mona was working through the conflicts inherent in being an accomplished artist, while also desiring a husband and family. The other exhibited piece was a portrait of an acquaintance, a Cuban sugar planter. Acceptance at the Salon was very difficult to attain, much less the awards of “honorable mention” for her work, doubly so for an unknown American woman as young as Mona, who was only 23.

These two years of study and hard work were climaxed by an exhibit at Le Salon des Beaux Arts in which two of her pieces were accepted. One, a life-sized model called “The Maiden,” was a figure of a young woman, blindfolded and struggling with the bonds of conventions. Mona called it “The Soul Striving.” Already in her work, Mona was working through the conflicts inherent in being an accomplished artist, while also desiring a husband and family. The other exhibited piece was a portrait of an acquaintance, a Cuban sugar planter. Acceptance at the Salon was very difficult to attain, much less the awards of “honorable mention” for her work, doubly so for an unknown American woman as young as Mona, who was only 23.

Several important orders followed the exhibit. Young as Mona was, her reputation as a sculptress was soon established. Who’s Who now recorded her among the artists of Paris, and her work was receiving more than passing notice on both sides of the Atlantic

Mona’s development as an artist was furthered spending a summer touring Italy. There she spent a great deal of the time in Florence and Rome viewing the works of Michelangelo, her “adopted patron.”

Sometime after the Italy trip, Mona received a book from her mother. It was a book of poetry written by a young American poet whom Ada had come to meet and by whom she was most impressed. Neihardt’s A Bundle of Myrrh “sent her spinning,” as Mona later recalled. Enchanted by the lyrics, she sent off an impulsive letter with the breathed prayer “Please, God, don’t let him be married!” When Neihardt replied, a correspondence began, of increasing importance to both. Neihardt was equally impressed with Mona’s sculpture. As marriage was contemplated, Neihardt apparently questioned the wisdom of marrying without meeting in person. Characteristic of the bold artist she had become, Mona replied: “Why should it be foolish to marry without seeing each other with the physical eyes?” she asked. “Is not the ideal more real than the material? She knew that “in the things that really counted, [they] were one.”

After six months of exchanging letters, Mona boarded a train to take her from New York to Omaha. Neihardt met her at the station with the marriage license in his pocket, struggled with a momentary panic at the silken elegance of the tall, modish figure emerging from the train. They were married the next day on November 29, 1908, with Neihardt’s mother as the only guest.

Mona, who had grown up in luxury, had no acquaintance with housework, didn’t even know a dime from a half-dollar, came out to a new country half a world away, moved into a small house without central heating, electricity, or plumbing, and exclaimed “Oh, John, what a darling cubby-hole!” The transition to married life couldn’t have been easy, for Mona had to learn even the most elementary principles of cooking and cleaning… and considered herself the most fortunate woman alive.

Mona loved her new life. She felt great satisfaction in achieving fine textured bread or beans that did not burst their jars. She learned a lot from her mother in law, but also from her husband. As she said years later in an interview: “Learning to cook was my greatest task. My husband helped me. He has camped out a great deal. I was proudest when the fruit and vegetables decided to stay in the can.” Children and grandchildren would remember her as a wonderful cook.

Mona wanted to share her husband’s life. On one occasion she insisted on walking with him ten miles to see a wrestling match. Her dress-shoe-confined feet hurt her so much that on the return trip Neihardt traded shoes with her and finished the walk in her heels. This anecdote is almost symbolic of the mutual support given to each other throughout their lives.

Bancroft welcomed Mona. One day in the local grocery store she impulsively caught up a chunk of butter and molded it into a figure. The owners set the figure inside the glass door of the refrigerator and for days displayed it proudly to their customers. Neihardt built Mona a small studio room with a north skylight, and they laughed together at the passing farmer who shook his head over the strange poet who didn’t know where to put windows in a house. Mona began a portrait bust of her husband, and their life became a routine of active days, followed by long leisurely evenings of reading and talk. And what talks they must have been! Mona’s tutelage under demanding sculpture masters had given wings of freedom to her thinking, and she was a good match in intellect to her husband. Mona was always frank and true to what she believed. When the poet would read to her what he had written that day, she would reply “Oh, bully, John” if she thought the lines were good. If she didn’t think so, she wouldn’t say much and John would go back into his study and change them.

Bancroft welcomed Mona. One day in the local grocery store she impulsively caught up a chunk of butter and molded it into a figure. The owners set the figure inside the glass door of the refrigerator and for days displayed it proudly to their customers. Neihardt built Mona a small studio room with a north skylight, and they laughed together at the passing farmer who shook his head over the strange poet who didn’t know where to put windows in a house. Mona began a portrait bust of her husband, and their life became a routine of active days, followed by long leisurely evenings of reading and talk. And what talks they must have been! Mona’s tutelage under demanding sculpture masters had given wings of freedom to her thinking, and she was a good match in intellect to her husband. Mona was always frank and true to what she believed. When the poet would read to her what he had written that day, she would reply “Oh, bully, John” if she thought the lines were good. If she didn’t think so, she wouldn’t say much and John would go back into his study and change them.

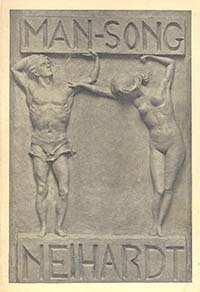

In 1909, Neihardt’s second volume of poetry entitled Man-Song was published with a bas-relief cover designed and sculpted by Mona. From studying this beautiful bas-relief, it is easy to see that this was a watershed moment for Mona, then 25. You see the poet in all his power and strength looking up into the heavens (for inspiration?) while the woman, the sculptress herself, with head bowed, reaching over to her husband in connection and support of his art, uses her meager physical strength to support his dream. Mona, the soul of self-sacrifice, felt that her husband’s art was greater than her own and had silently vowed to dedicate herself to it.

In 1909, Neihardt’s second volume of poetry entitled Man-Song was published with a bas-relief cover designed and sculpted by Mona. From studying this beautiful bas-relief, it is easy to see that this was a watershed moment for Mona, then 25. You see the poet in all his power and strength looking up into the heavens (for inspiration?) while the woman, the sculptress herself, with head bowed, reaching over to her husband in connection and support of his art, uses her meager physical strength to support his dream. Mona, the soul of self-sacrifice, felt that her husband’s art was greater than her own and had silently vowed to dedicate herself to it.

And then the babies came: Enid in 1911, Sigurd in 1912, Hilda in1916 and Alice in 1921. Family life moved along peacefully. Mona cooked, sewed, canned, and modeled heads of the children when she could find the time. Sometimes Grandma Neihardt took over the household chores to give Mona undisturbed time in the studio. Mona had won the respect of her work-brittle mother-in-law by her industry.

In a 1919 interview, Mona gave her position on reconciling her art with the demands of family life. She commented that a woman artist can well afford to pause in her career to bring up her children. She is remembered as always doing sweet things like having ice cream ready when the kids came back from swimming with their father. She loved holidays and built ceremony into celebrations. Christmas was especially wonderful, with the family gathered about the Christmas tree singing German Christmas carols.

But as her children grew, she intended to begin her work again. In 1919 the bust of a college president was under way and a group for a statehouse was under consideration. Mona wished to make her reputation match her husband’s. We have no record of either piece having been completed, probably falling by the way side during Mona’s struggle to survive a miscarriage in that year.

While caring for her own 4 children, Mona consciously and unconsciously observed their expressions, actions and moods. Sometimes while the children were reading or playing she would go up to them, move their arms this way or that, then say ‘Thank you’ and walk away. Mona would look at a subject during conversation with unusual intensity. She was dissecting the construction of the face or body for later use. When time permitted, she used her training in sculpting from memory and began making busts or miniature portraits of the children, and later the grandchildren, in various moods and positions. The sculptress/mother found that by spending several hours with the child, playing with him, she could enter into his consciousness and thereby capture his spirit. Then she could produce a model which not only resembled the original in very physical detail, but more importantly, captured the child’s own distinct personality, just as Rodin had taught her to do.

While caring for her own 4 children, Mona consciously and unconsciously observed their expressions, actions and moods. Sometimes while the children were reading or playing she would go up to them, move their arms this way or that, then say ‘Thank you’ and walk away. Mona would look at a subject during conversation with unusual intensity. She was dissecting the construction of the face or body for later use. When time permitted, she used her training in sculpting from memory and began making busts or miniature portraits of the children, and later the grandchildren, in various moods and positions. The sculptress/mother found that by spending several hours with the child, playing with him, she could enter into his consciousness and thereby capture his spirit. Then she could produce a model which not only resembled the original in very physical detail, but more importantly, captured the child’s own distinct personality, just as Rodin had taught her to do.

Mona was true to her “man-song” pledge. Neihardt appreciated her intense loyalty, referring to her as the most loyal person he’d ever known. Though household duties preempted her time for sculpture, she devoted herself to the family and the furthering of her husband’s work. She accepted the difficulties with good grace. She did her best to arrange the household for the least possible inconvenience to a poet in need of undisturbed solitude. It was she who urged the poet, yearning to move past the lyrics which she thought were among his best work, to achieve an enduring epic. It was Mona who turned his thinking away from the French Revolution as a subject matter and encouraged him to write about what he knew. They began the Cycle of the West in 1912 and endured the trial together until its completion in 1941. I say “they began the Cycle”, because I do not believe John could have written it without Mona’s willing sacrifices, without her willingness repeatedly to move away from circumstances of relative prosperity to financial constraints that allowed her husband more writing time. To keep a modicum of money coming in yet maximize the poet’s dedicated time to writing, the family moved to Minneapolis in 1912, back to Bancroft around 1914, to Branson in 1920, where the family first had electricity, to St. Louis in 1926 where Neihardt joined the Post Dispatch, back to Branson in 1930 for a focus on the writing of the Song of the Messiah. In one of her letters to Neihardt while he was away on a long and tiring lecture tour in 1923 she exclaimed: “You must not think for one minute that I feel the least bit dissatisfied with my lot. Indeed I don’t. I know how lucky I am to be your wife, darling, great, good man that you are. I often wish I were prettier, and this and that for you… But when I think that you are satisfied with me, then I am always happy.”

During the Branson period of the 30’s, Mona sculpted Hilda and Alice and modeled little figures of children that she called Ozark Babies. She became acquainted with Rose O’Neil, creator of the kewpie, shown here with a sculpture of granddaughter Elaine. She also finished a new bust of John of which she wrote Enid “It is Daddy, and the Poet Neihardt in one!” But this bust met the fate of most of her others. She decided she could do better and destroyed it.

During the Branson period of the 30’s, Mona sculpted Hilda and Alice and modeled little figures of children that she called Ozark Babies. She became acquainted with Rose O’Neil, creator of the kewpie, shown here with a sculpture of granddaughter Elaine. She also finished a new bust of John of which she wrote Enid “It is Daddy, and the Poet Neihardt in one!” But this bust met the fate of most of her others. She decided she could do better and destroyed it.

In 1935, the Song of the Messiah was completed. Her joy was indescribable when he dedicated the Song to her “Just think of it”, she wrote Enid, “The greatest and noblest and best of all his poems—to me!!

In May of 1936, Mona was critically ill for some weeks. Neihardt was working at the time in St. Louis again. But typical of Mona, she worried about the expense of her illness; the savings for the writing of Jed Smith were being spent on a nurse for her and she agonized over the summer suit and hat that Neihardt needed. “For my sake buy yourself a brand new good Panama. You have the harder end of this, not I,” she wrote him several times. She recovered, designed new Ozark Babies for candle sticks, made another bust of Neihardt, later destroyed it and counted her blessings. In 1937 an adoring and appreciative Neihardt wrote one of the children: “Do you know that look Mama gets? Roses in sunlight!”

In additional attempts to create art to sell, Mona cast her Ozark Babies to place in gift shops and designed a small model for sale as a souvenir of the Shepherd of the Hills country. She also attempted to sell her sea nymph in Cincinnati. Of the sea nymph she wrote concert pianist son Sigurd: “There can be such a thing as music in clay that disturbs no one, and that is what my present sea nymph is to me. The surf forms are the left hand accompaniment and the nymph is the theme song.” But times were had for marketing art in the ’30’s.

In 1940, after 33 years of marriage, Neihardt was continuing work on the Song of Jed Smith. Mona wrote of that time: “He used to read me every day what he wrote, and now it is really wonderful that the time has come when we can again be quiet and united in his work.” But “no one can guess what a long, hard pull that Cycle has been.” Difficult as those times were, Mona had the satisfaction of understanding her contribution: “John is the pure gold and his the work wrought, but I am the alloy that has given the gold its necessary strength

In 1947 John and Mona moved to Columbia, Missouri and there bought the Skyrim farm. Mona delighted in having her children and grandchildren close by. The older grandchildren remember having tea and cookies after naptime, and being taught old world manners.

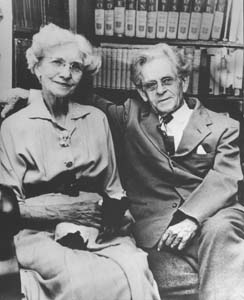

As he always did, John arranged for her to have a studio and she began working at sculpture again. A new somersault baby modeled from Robin was added to the set. In 1949 Mona completed a new bust of Neihardt and was sufficiently satisfied with it to say “It is Gaki!” using the grandchild inspired nickname. In 1949 Neihardt accepted an appointment at the University of Missouri, Columbia. In 1957, Mona herself sat in on one term of the class, her face ecstatic with pride. In fact observers always commented on the glow of her face as she sat in the audience during one of Neihardt’s lectures or poetry readings. To Sigurd she queried, paraphrasing the biblical passage, “Why should John and I be so fortunate? Is it maybe because we both have honestly sought first the higher values and ‘all these things shall be added unto you’?”

As he always did, John arranged for her to have a studio and she began working at sculpture again. A new somersault baby modeled from Robin was added to the set. In 1949 Mona completed a new bust of Neihardt and was sufficiently satisfied with it to say “It is Gaki!” using the grandchild inspired nickname. In 1949 Neihardt accepted an appointment at the University of Missouri, Columbia. In 1957, Mona herself sat in on one term of the class, her face ecstatic with pride. In fact observers always commented on the glow of her face as she sat in the audience during one of Neihardt’s lectures or poetry readings. To Sigurd she queried, paraphrasing the biblical passage, “Why should John and I be so fortunate? Is it maybe because we both have honestly sought first the higher values and ‘all these things shall be added unto you’?”

Though she did not live to see it, Mona’s portrait busts were cast in bronze to become permanent memorials to Neihardt both in Missouri and Nebraska.

Mona Martinsen Neihardt died in the spring of 1958 in Columbia, Missouri. Prescient as she had always been, Mona seemed to know some time before her last illness that her days were few. As Neihardt wrote afterward, “Mona was quietly preparing for the great change, and I knew it.” She once told Sigurd, “I want to be a real help till the day I go to the next world — Amen.” And she was. During the last year of her life her friends could see a radiance in her as if her spirit burned through a frail shell. She spoke calmly of death and gave Neihardt instructions about her funeral: he was to speak and read lyrics. When the time came he spoke not to the congregation but directly to Mona and read the lyrics she had requested, “When I Have Gone Weird Ways,” and “I:Envoi.” Sigurd played the Bach prelude that had always made Mona “feel sure that the universe is well ordered and everything is all as it should be,” and Hilda sang a “song of affirmation” her mother had loved. Wrote an old friend “I always had the feeling that Mona felt her husband was a gift from the Divine Creator and knew herself blessed, for she loved her Skyrim home and was happy when her husband was honored.” Mona’s devotion to her husband and children had become legend.

Mona Martinsen Neihardt died in the spring of 1958 in Columbia, Missouri. Prescient as she had always been, Mona seemed to know some time before her last illness that her days were few. As Neihardt wrote afterward, “Mona was quietly preparing for the great change, and I knew it.” She once told Sigurd, “I want to be a real help till the day I go to the next world — Amen.” And she was. During the last year of her life her friends could see a radiance in her as if her spirit burned through a frail shell. She spoke calmly of death and gave Neihardt instructions about her funeral: he was to speak and read lyrics. When the time came he spoke not to the congregation but directly to Mona and read the lyrics she had requested, “When I Have Gone Weird Ways,” and “I:Envoi.” Sigurd played the Bach prelude that had always made Mona “feel sure that the universe is well ordered and everything is all as it should be,” and Hilda sang a “song of affirmation” her mother had loved. Wrote an old friend “I always had the feeling that Mona felt her husband was a gift from the Divine Creator and knew herself blessed, for she loved her Skyrim home and was happy when her husband was honored.” Mona’s devotion to her husband and children had become legend.

Mona’s enduring gift was un-stinted love and the appreciative acceptance of life as it came. After the children would recite the last lines of a family grace that the poet had written for the kids “Thank you for the birds that sing, thank you God for everything,” Mona would toss her head and say “And I do mean everything, the good and the bad!” Neihardt was thankful that he had dedicated The Messiah to her with his own lines “His woman was a mother to the Word.” He wrote, “That was not sentiment. Not long ago she and I were talking about our life and the Cycle, and I said “Well by God, we did it, didn’t we? And she said ‘Yes, Daddy, by God we did.'”