The Book of a Seer

Time and Change. By John Burroughs

IN an introduction to his latest collection of essays, Mr. Burroughs says: “I suspect that in this volume my reader will feel that I have given him a stone when he asked for bread, and his feeling in this respect will need no apology. I fear there is more of the matter of hard science and scientific speculation in this collection than of spiritual and esthetic nutriment. But I do hope the volume is not entirely destitute of the latter.”

IN an introduction to his latest collection of essays, Mr. Burroughs says: “I suspect that in this volume my reader will feel that I have given him a stone when he asked for bread, and his feeling in this respect will need no apology. I fear there is more of the matter of hard science and scientific speculation in this collection than of spiritual and esthetic nutriment. But I do hope the volume is not entirely destitute of the latter.”

There is an engaging element of naivete in this passage. It seems not to have occurred to Mr. Burroughs that he is incapable of treating any theme without casting upon it the calm illumination of his own fine spirit. A dissertation on conic sections by this sweet old seer would inevitably take on a spiritual tone.

In a general way, the essays here collected are concerned with geology; but it is not the purely factual aspect that is presented. As a scholar might read a fine old classic, penciling wise observations on the margin as he reads, so Mr. Burroughs reads the story of the rise of man from the geological strata of the earth, and humanizes the story for us.

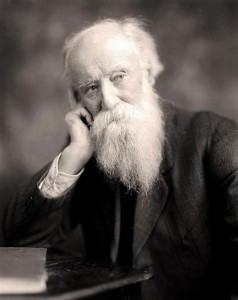

It is a function of the seer to deduce truth from fact, wisdom from knowledge; and John Burroughs is a seer. America has produced no finer soul than his.

The first essay, “The Long Road,” is easily the greatest in the book, although all are strong and interesting. In it is traced the long evolutionary process through which man has come to his present state. There is not one new fact in it. The world has long since become familiar with the fundamentals of this thinking. But never before in so small a compass has so tremendous a picture been given of the long way up from the primeval ooze when “God moved upon the face of the waters.” It is indeed a terrible vision at first glance. A lesser man than Burroughs might easily have erred in the direction of atheism, might easily have come face to face at last with pessimism, and accepted it in despair. But Burroughs finds God in it all and a strengthening of faith.

“That man should have been brought into existence by the fiat of an omnipotent power,” he says, “is less an occasion for wonder than that he should have worked his way up from the lower non-human forms. That the manward impulse should not have been lost in all the appalling vicissitudes of geologic time is the wonder of wonders.”

Later in the same essay, we come upon this question, which many less spiritual seekers after truth have refused to consider: “Through evolution we see creation in travail pains for millions of years to bring forth the varied forms of life as we know them; but the mystery of the inception of this life, and of the origin of the laws that have governed its development, remain. It is quite impossible for me to believe that fortuitous variation could have resulted in the evolution of man.”

There is one passage in this essay that deserves to be written on ivory with letters of gold. It is profoundly significant in many directions; cryptic and yet supremely eloquent, touching, as it does, biology, history, religion, sociology, the hard facts of now and the visions of eternity:

“Experimenting and experimenting endlessly, taking a forward step only when compelled by necessity — this is the way of Nature — experimenting with eyes, with ears, with teeth, with limbs, with feet, with toes, with wings, with scales and armors, hitting upon the backbone only after long trials with other forms, hitting upon the movable eye only after long ages of other eyes, hitting on the mammal only after long ages of egg-laying vertebrates, hitting on the placenta only recently — experimenting all around the circle, discarding and inventing, taking ages to perfect the nervous system, ages and ages to develop the centralized ganglia, the brain. First life was like a rabble, a mob, without thought or head; then slowly organization went on, as it were, from family to clan, from clan to tribe, from tribe to nation, or centralized government — the brain of man — all parts duly subordinated and directed — millions of cells organized and working on different functions to one grand end — co-operation, fraternization, division of labor, altruism.”

The last sentence is probably unsurpassed as a brief statement of universal progress.

In the eassay on “The Gospel of Nature,” Mr. Burroughs says: “But I am not preaching much of a gospel, am I? Only the gospel of contentment, of appreciation, of heeding simple, near-by things — a gospel, the burden of which is still love, but love that goes hand in hand with understanding.”

This, together with one other passage, may be said to sum up the life philosophy of John Burroughs, as set forth in this book:

“For my part, as I grow older I am more and more inclined to reduce my baggage, to lop off superfluities. I become more and more in love with simple things and simple folk — a small house, a hut in the woods, a tent on the shore. Show and splendor fix the attention upon false values, they set up a false standard of beauty, they stand between me and the real feeders of character and thought.”

It is an old philosophy — the first and the last; one which America needs today. Jesus preached it, and Socrates. It is the philosophy that involves restraint, the limitation of one’s desires rather than the gratification of them. Perhaps it is only a way of “laying up treasures in heaven.”