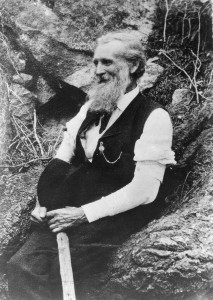

Another Muir Book

A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf. By John Muir

IT WILL be remembered by those who have read Muir’s “Story of My Boyhood and Youth” and “My First Summer in the Sierra,” that a large gap existed between the two volumes. Now, at length, the gap is bridged by the publication of Muir’s journal of a botanizing trip afoot from Indiana to Florida undertaken in the autumn of 1867. Although the young naturalist had botanized along the shores of the great lakes in Wisconsin and Michigan previous to this southern excursion, it nevertheless may be said that his career began in earnest with this long pedestrian tour from Jeffersonville on the Ohio river through the forests of central Kentucky, over the Cumberland mountains and across Georgia to Savannah. Then, for the first time, he displayed to the full what might, oddly enough perhaps, be called the gentle spirit of daring which was one of his chief characteristics to the end. His route to the sea was purposely chosen through the least civilized parts of the states he crossed, and at that time it was far from safe to make such a trip, owing to the numerous bands of outlaws that infested the wilderness. Muir’s narrative of his journey gives one the impression that he did not thoroughly appreciate the dangers of the undertaking, so absorbed was he in the beauties of nature along the way.

IT WILL be remembered by those who have read Muir’s “Story of My Boyhood and Youth” and “My First Summer in the Sierra,” that a large gap existed between the two volumes. Now, at length, the gap is bridged by the publication of Muir’s journal of a botanizing trip afoot from Indiana to Florida undertaken in the autumn of 1867. Although the young naturalist had botanized along the shores of the great lakes in Wisconsin and Michigan previous to this southern excursion, it nevertheless may be said that his career began in earnest with this long pedestrian tour from Jeffersonville on the Ohio river through the forests of central Kentucky, over the Cumberland mountains and across Georgia to Savannah. Then, for the first time, he displayed to the full what might, oddly enough perhaps, be called the gentle spirit of daring which was one of his chief characteristics to the end. His route to the sea was purposely chosen through the least civilized parts of the states he crossed, and at that time it was far from safe to make such a trip, owing to the numerous bands of outlaws that infested the wilderness. Muir’s narrative of his journey gives one the impression that he did not thoroughly appreciate the dangers of the undertaking, so absorbed was he in the beauties of nature along the way.

From Savannah, he took ship to Fernandina, Fla., and from there he struck fearlessly across the swamp lands to Cedar Keys on the west coast. Here he was stricken with fever on the eve of his departure for the wildernesses of the Amazon and Orinoco. This proved to be a very fortunate circumstance, for he was not equipped to explore the tropical jungles, and had he attempted to do so the world doubtless would have been the poorer, lacking the memory of so great and unselfish a career.

It was immediately after his Florida experience that he set out for California by way of the isthmus, arriving at San Francisco in April, 1868, at which point the journal ends. But the editor, William Frederic Bade, has been able to furnish the last span of the bridge by excerpting from a letter a summary account of Muir’s first visit to the Yosemite, which takes the reader to the year 1869, when the “First Summer in the Sierra” begins.

Considering that the journal here given to the world was written a half century ago, it might be inferred that the book is to be regarded as rather a juvenile attempt. But that is not the case. Here is the same John Muir that thousands have learned to love and admire — the same courage, the same enthusiasm, the same wonderful devotion to science, and not a little of the remarkable literary quality that is to be found in the later works.