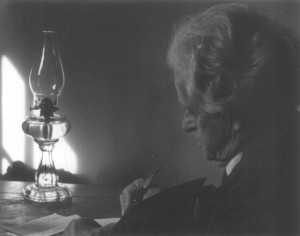

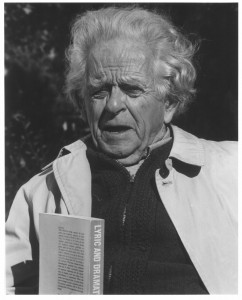

A visionary thinker with keen spiritual insight, John Neihardt left us a rich inheritance of wisdom and a legacy of understanding. He was the author of some twenty-five volumes of poetry, fiction, and philosophy. If you don’t know Neihardt, discover him!

Until I was 12 years old, I was sure that I, John Neihardt, was going to be an inventor. I had made considerable progress when a strange dream changed the direction of my life and resulted in the focusing of all my energies on poetry and creative writing generally. I cannot say why the dream, the strangest I ever had, could have so much influence, but so it was. This happened in the fall when I was 11. When I was 12 years old, I wrote my first verses. They were pretty bad, I can tell you, and my face still burns when I think of them. But it was not long before I knew they were worthless and burned them. All my writing up to my 16th year suffered the same fate, for I knew I was growing, and I wanted nothing but my best to survive me if I should die early.

My first printed book, The Divine Enchantment, was completed when I was 16 and printed when I was 19. Within a year thereafter I burned nearly the whole edition of 500 copies. I think there was something of jealous love in my motive, for it was a rather remarkable little book. I felt that I would soon outgrow it, and I did not want it to suffer the gaze of alien and unfriendly eyes.

With the appearance of The Divine Enchantment in book form, I felt that my apprenticeship had ended. I had written much short verse, and two long heroic narrative poems in rather respectable blank verse. The hero of these poems was a half-human caveman of the Stone Age. And the heroine — well, I have wished I could see my blank verse description of that Lady of the Caves. She must have been a sensation, and I am sure (recalling from Marlowe’s Helen and her thousand ships) that her face could have launched a considerable flotilla of war canoes. All this had been most precious to me while I was writing it, and the hurt was grueling when I saw it go up in flames and end in ashes. But, along with the hurt, there was a sense of triumph, too, for I felt that I was, now at last, out of the woods and definitely on my way to wherever I was going.

This brings me to what I consider a matter of prime importance in any discussion of creative writing — the need for self-criticism and the means of developing the ability to evaluate one’s work. I had made a great discovery — a very great discovery. Many had made this discovery before me, but it was new and thrilling to me. I will tell you how it happened.

When it became clear that my heart was set on being a poet, my sisters gave me a cheap paperback copy of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, which they had obtained as a premium for saving soap wrappers. That little book proved to be The Great Front Gate to an enchanted world of wonder, wisdom, and beauty — the world of great literature. One book led to another until I came to realize that I was associating with masters who knew how to do what I was attempting to do. After I had listened to those masters and then turned back to my first crude efforts, I was shamed and shocked by what I had done.

As a result of my growing acquaintance with such masters, there had been some development of that mysterious quality of awareness that we know as Taste. Taste in some degree, is often inherent in the individual, but its necessary development is made possible only by familiarity with superior work.

There are fashions in literature as in everything else, and they change from time to time, from country to country, from race to race. But what is essential to the quality of greatness in literature does not change, for it is not primarily a matter of technique or style or even dominant social concepts. It is a matter of the great moods that have dominated the human spirit throughout mankind’s adventure on this planet; and these moods outlast the Horatian “tooth of time and tongue of fire.” Great works of literature have endured for the reason that they deal in some measure with characteristic moods which occur in all races and times, and relate us all in an unbroken descent throughout the centuries. I had this in mind when I wrote in one of my lyrics:

With Eld thy chain of days is one;

The seas are still Homeric seas;

The skies still glow with Pindar’s sun,

The stars of Socrates!

The passions and struggles, the hopes and failures, the triumphs and defeats, the joys and heartaches of men and women are what they were three thousand years ago, and shall be so, after the moon shall have become a popular summer resort. To note an extreme example by way of emphasis, the death of Hector on the embattled Trojan plain and the mourning of Priam, his father, differ in no significant manner from the death of our Crazy Horse at our own Fort Robinson [Nebraska] and the mourning of his old father and mother.

Sometimes such enduring human moods may dominate whole tribes or nations, and sometimes only one lone individual — but the principle involved is the same. World literature is the vehicle of race consciousness. Through a knowledge of world literature the individual may share vicariously in the experience of men in all times and countries; and surely this is education in the broader sense. For what is education but the process of expanding the individual consciousness to include as much of race consciousness as possible, with understanding and universal sympathy as ideal objectives?

Here then, is the chief point I want to emphasize for developing young people who will produce some of our literature of the future and (why not?) some of its masterpieces too. Enrichment of personality, increased understanding of human affairs, and wider sympathy — these would justify whatever time might be given to the reading of world literature. But even mere acquaintance with greatness in enduring literature of the past would be of great value to the developing writer — especially in times like ours.

Here then, is the chief point I want to emphasize for developing young people who will produce some of our literature of the future and (why not?) some of its masterpieces too. Enrichment of personality, increased understanding of human affairs, and wider sympathy — these would justify whatever time might be given to the reading of world literature. But even mere acquaintance with greatness in enduring literature of the past would be of great value to the developing writer — especially in times like ours.

Since 1912, when the great wave of impressionism struck us over here in the United States, we have been living in a state of cultural anarchy. Impressionism, as I use the term, may be defined as the tendency to repudiate all standards of judgment that grew out of accumulated race-experience, and the substitution of individual caprice as a guide. In whatever phase of our culture you may examine, you will find this anarchic mood dominant. If that mood were to be described in two words, those two words might well be “anything goes.” Start with the “Hippies” or the wide-spread rioting, or anywhere else you like — with poetry, music, painting, sculpture, dancing, morals or social relations generally — and that dominant mood will be apparent. Our entire scale of values is in a higgledy-piggledy condition.

But it is not my intention to disparage our time. It is our time to live — the only time we have; and in spite of its eccentricities, it is, in some respects, a very great time, especially in its scientific conquest of our physical world. A great social process is in progress, no doubt, and what we see may well be, and most probably is, a transition toward some new social and cultural integration. But it is desirable that the developing personality of a young writer should have some means of cultural orientation — some way of knowing that his moment in time is just that — only his moment in time; and that he needs a working knowledge of the best that has been done in his chosen field as a defense against the grotesque and comic vagaries of his myopic and pitifully troubled day.

At parting, I want to say that of all the good things I have experienced in a long life, love is easily the best. But a close second is the satisfaction of the instinct of workmanship — the exaltation that results from having done one’s best, and seeing that it is good. Carlyle once expressed the idea when he remarked, “One Should write as though God were looking over one’s shoulder.” It is this exalting satisfaction that I wish for you in full measure.

And when you are working on that great book for which an impatient world has been waiting all these weary centuries, remember that there are many books in the world already, that a surprising number of them are really quite good, and that there is no need for hurry in producing another bad one.