The following was written by John G. Neihardt in 1948 as an introduction to his book, The Twilight of the Sioux. This book is comprised of the last two of his Songs from A Cycle of the West, The Song of the Indian Wars, and The Song of the Messiah.

In 1912, at the age of 31, I began work on the following cycle of heroic Songs, designed to celebrate the great mood of courage that was developed west of the Missouri River in the nineteenth century. The series was dreamed our, much of it in detail before I began; and for years it was my hope that it might be completed at the age of 60—as it was. During the interval, more than five thousand days were devoted to the work, along with the fundamentally important business of being first a man and a father. It was planned from the beginning that the five Songs, which appeared at long intervals during a period of twenty-nine years, should constitute a single work. They are offered as such.

In 1912, at the age of 31, I began work on the following cycle of heroic Songs, designed to celebrate the great mood of courage that was developed west of the Missouri River in the nineteenth century. The series was dreamed our, much of it in detail before I began; and for years it was my hope that it might be completed at the age of 60—as it was. During the interval, more than five thousand days were devoted to the work, along with the fundamentally important business of being first a man and a father. It was planned from the beginning that the five Songs, which appeared at long intervals during a period of twenty-nine years, should constitute a single work. They are offered as such.

The period with which the Cycle deals was one of discovery, exploration and settlement—a genuine epic period, differing in no essential from the other great epic periods that marked the advance of the Indo-European peoples out of Asia and across Europe. It was a time of intense individualism, a time when society was cut loose from its roots, a time when an old culture was being overcome by that of a powerful people driven by the ancient needs and greeds. For this reason only, the word ‘epic’ has been used in connection with the Cycle; it is properly descriptive of the mood and meaning of the time and of the material with which I have worked. There has been no thought of synthetic Iliads, and Odysseys, but only of the richly human sage-stuff of a country that I knew and loved, and of a time in the very fringe of which I was a boy.

This period began in 1822 and ended in 1890. The dates are not arbitrary. In 1822 General Ashley and Major Henry led a band of a hundred trappers from St. Louis, “the Mother of the West”, to the beaver country of the upper Missouri River. During the following year a hundred more Ashley-Henry men ascended the Missouri. Out of these trapper bands came all the great continental explorers after Lewis and Clark. It was they who discovered and explored the great central route by way of South Pass, from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean, over which the tide of migration swept westward from the 40’s  onward.

onward.

The Song of Three Friends and The Song of Hugh Glass deal with the ascent of the river and with characteristic adventures of Ashley-Henry men in the country of the upper Missouri and the Yellowstone.

The Song of Jed Smith follows the first band of Americans through South Pass to the Great Salt Lake, the first band of Americans to reach Spanish California by and overland trail, the first white men to cross the great central desert from the Sierras to Salt Lake.

The Song of the Indian Wars deals with the period of migration and the last great fight for the bison pastures between the invading white race and the Plains Indians—the Sioux, the Cheyenne and the Arapahoe.

The Song of the Indian Wars deals with the period of migration and the last great fight for the bison pastures between the invading white race and the Plains Indians—the Sioux, the Cheyenne and the Arapahoe.

The Song of the Messiah, is concerned wholly with the conquered people and the worldly end of their last great dream. The period closes with the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890, which marked the end of Indian resistance on the Plains.

It will have been noted from the foregoing that the five Songs are linked in chronological order; but in addition to their progress in time and across the vast land, those who may feel as I have felt while the tales were growing may not a spiritual progression also—from the level of indomitable physical prowess to that of spiritual triumph in apparent worldly defeat. If any vital question be suggested in The Song of Jed Smith, of instance, there may be those who will find its age-old answer once again in the final Song of an alien people who also were men, and troubled.

But, after all, “the play’s the thing”; and while it is true that a knowledge of Western history and the topography of of the country would be very helpful to a reader of the Cycle, such knowledge is not indispensable. For here are tales of men in struggle, triumph and defeat.

Those readers who have not followed the development of the Cycle may wish to know, and are entitled to know, something of my fitness for the task assumed a generation ago an now completed. To those I may say that I did not experience the necessity of seeking material about which to write. The feel and mood of it were in the blood of my family, and my early experiences aroused a passionate awareness of it. My family came to Pennsylvania more than a generation before the Revolutionary War, in which fourteen of us fought; and, crossing the Alleghenies after the war, we did not cease pioneering until some of us reached Oregon. Any one of my heroes,, from point of time, could have been my paternal grandfather, who was born in 1801.

Those readers who have not followed the development of the Cycle may wish to know, and are entitled to know, something of my fitness for the task assumed a generation ago an now completed. To those I may say that I did not experience the necessity of seeking material about which to write. The feel and mood of it were in the blood of my family, and my early experiences aroused a passionate awareness of it. My family came to Pennsylvania more than a generation before the Revolutionary War, in which fourteen of us fought; and, crossing the Alleghenies after the war, we did not cease pioneering until some of us reached Oregon. Any one of my heroes,, from point of time, could have been my paternal grandfather, who was born in 1801.

My maternal grandparents were covered-wagon people, and at the age of five I was living with them in a sod house on the upper Solomon in western Kansas. The buffalo had vanished from that country only a few years before, and the signs of them were everywhere. I have helped, as a little boy could, in “picking cow-chips” for winter fuel. If I write of hot-winds and grasshoppers, of prairie fires and blizzards, of dawns and noons and sunsets and nights, of brooding heat and thunderstorms in the vast lands, I knew them early. They were the vital facts of my world, along with the talk of the old-timers who knew such fascinating things to talk about.

My maternal grandparents were covered-wagon people, and at the age of five I was living with them in a sod house on the upper Solomon in western Kansas. The buffalo had vanished from that country only a few years before, and the signs of them were everywhere. I have helped, as a little boy could, in “picking cow-chips” for winter fuel. If I write of hot-winds and grasshoppers, of prairie fires and blizzards, of dawns and noons and sunsets and nights, of brooding heat and thunderstorms in the vast lands, I knew them early. They were the vital facts of my world, along with the talk of the old-timers who knew such fascinating things to talk about.

I was a very little boy when my father introduced me to the Missouri River at Kansas City. It was flood time. The impression was tremendous, and a steadily growing desire to know what had happened on such a river led me directly to my heroes. Twenty years later, when I had come to know them well, I built a boat at Fort Benton, Montana, descended the Missouri in low water and against head winds, dreamed back the stories men had lived along the river, bend by bend. This experience is set forth in The River and I.

In northern Nebraska I grew up at the edge of the retreating frontier, and became intimately associated with the Omaha Indians, a Siouan people, when many of the old “long-hairs” among them still remembered vividly the time that meant so much to me. We were good friends. Later, I became equally well acquainted among the Oglala Sioux, as my volume, Black Elk Speaks, reveals; and I have never been happier than while living with my friends among them, mostly unreconstructed “long-hairs” sharing, as one of them, their thoughts, their feelings, their rich memories that often reached far back into the world of my Cycle.

When I have described battles, I have depended far less on written accounts than upon the reminiscences of men who fought in them—not only Indians, but whites as well. For, through many years, I was privileged to know many old white men, officers and privates, who had fought in the Plains Wars. Much of the material for the last two Songs of the series came directly from those who were themselves a part of the stories.

For the first three Songs, I was compelled to depend chiefly upon early journals of travel and upon an intimate knowledge of Western history generally. But while I could not have known my earlier heroes, I have known old men who had missed them, but had known men who knew some of them well; and such memories at second hand can me most illuminating to one who knows the facts already. For instance, I once almost touched even Jedediah Smith himself, the greatest and most mysterious of them all, through an old plainsman who was an intimate friend of Bridger, who had been a comrade of Jed!

Such intimate contacts with soldiers, plainsmen, Indians and river men were were and integral part of my life for man years, and I cannot catalog them here. As for knowledge of the wide land with which the Cycle deals, those who know any part of it well will know that I have been there too.

Those who are not acquainted with early Western history will find a good introduction the the Cycle in Harrison dale’s The Ashley-Henry Men—or perhaps my own book, The Splendid Wayfaring.

I can see now that I grew up on the farther slope of a veritable “watershed of history”, the summit of which is already crossed, and in a land where the old world lingered longest. It is gone, and, with it, all but two or three of the old-timers, white and brown whom I have known. My mind and most of my heart are with the young, and with the strange new world that is being born in agony. But something of my heart stays yonder, for in the years of my singing about a time and a country that I loved, I note, without regret, that I have become an old-timer myself!

I can see now that I grew up on the farther slope of a veritable “watershed of history”, the summit of which is already crossed, and in a land where the old world lingered longest. It is gone, and, with it, all but two or three of the old-timers, white and brown whom I have known. My mind and most of my heart are with the young, and with the strange new world that is being born in agony. But something of my heart stays yonder, for in the years of my singing about a time and a country that I loved, I note, without regret, that I have become an old-timer myself!

The foregoing was set down in anticipation of some question that readers of good will, potential friends, might ask.

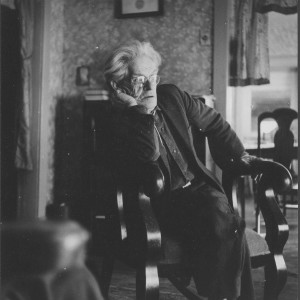

John G. Neihardt

Columbia, Mo. 1948